| Frying Pan Copper Mine Fairfax County, Virginia 1728- ca. 1732 |

|

by Debbie Robison January 25, 2016 |

|

Scientists with the US Geologic Survey wrote that the copper

found at this mine was hornfels copper, which is

found adjacent to diabase sheets in early Mesozoic basins, including the

Culpeper basin. Diabase is an igneous intrusion mined in the area for road bed

gravel, such as the gravel at Luck Stone Quarry. The Culpeper basin in Fairfax

County is located, roughly, west of Difficult Run and extends into Loudoun

County.[3]

|

| EARLY DISCOVERIES YIELD HOPE |

|

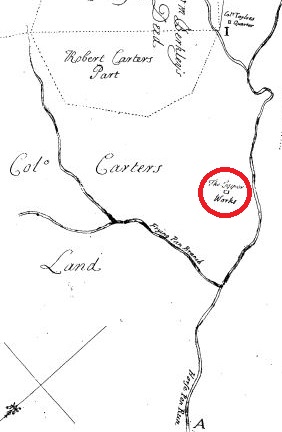

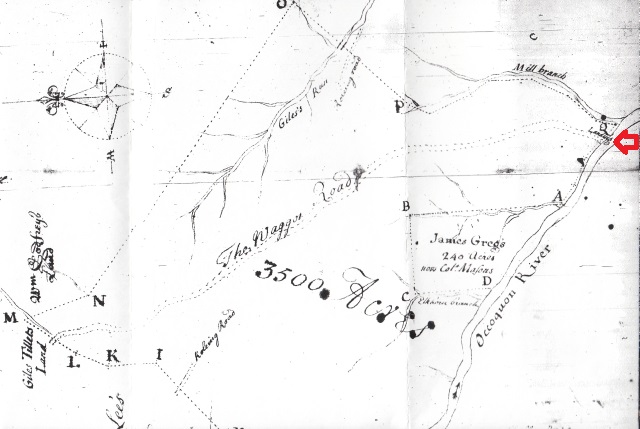

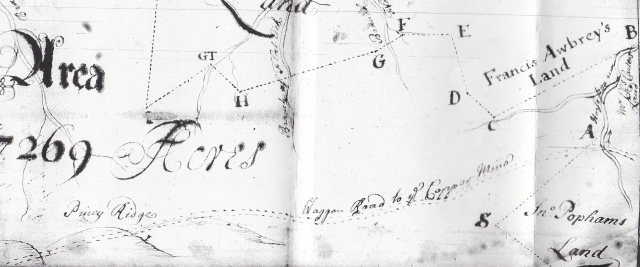

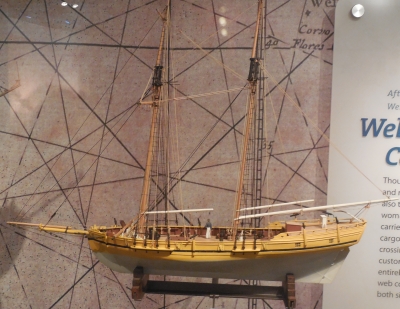

Some of the first ore that was found was shipped to London and Bristol for testing but the results were not promising, possibly to due the small sample size. As a result, in September 1729 Carter shipped a small barrel containing 106 pounds of ore in the Sarah to London merchant Edward Athawes for trials to obtain the value. Some of the copper was beaten in a bag and washed in Virginia and some was sent in lump form. Carter was unsure which sample would yield the most metal.[4] Carter was pleased with the results of the trial and made Athawes his agent in London. He requested that Athawes hire miners. Transportation was paid for at least two low-skilled diggers from London in return for their indentured service for four years.[5] Carter also entered into contractual agreements with three experienced miners from Falmouth. Additionally, Carter employed slave labor to work the mine.[6] As of April 1730, the Frying Pan Copper Mining Company “raised” enough ore to fill 50 casks weighing 400 lbs each. The casks were the size of tar barrels.[7] To facilitate shipping the ore, Carter obtained a grant for escheat land[8] on the Occoquan River where he built his Copper Mine Landing.[9] Ox Road, which still exists for much of its length, was improved between the mine and the landing. The landing was located about where the Occoquan Reservoir dam is located today.

Additional land of 875 acres was acquired half way between the landing and the mine where a post, called the Half Way House, was established for the change of horses.[10] The Half Way House was located just south of present-day George Mason University. In total, the Frying Pan Copper Mining Company acquired over 20,000 acres of land, much of it farmed by tenants.[11]

Casks of ore were conveyed in wagons down the Ox Road to the landing. But the problem Carter was having making a profit in copper mining was the cost of shipping the ore.In 1730 Carter wrote to his London agent that he wasn’t pleased with the bids he was getting for shipping the ore. The lowest rate a captain would offer was 15 pounds per cask and Carter didn’t think he could afford to ship at that cost.[12] Carter was also dissatisfied with the amount of ore that had been found. He requested Athawes to hire skilled miners to provide the expertise needed to find the copper. The greatest kindness you Can do us in this affair will be to procure a proper person skiled in Working these mines with a set of proper labourers Whose business has been to live undergound and whose trade hath been to rais these Ores without such assistance I am affeard the game will not main pay for the Candles. [13] The following month, Carter wrote to London merchant James Bradley requesting that he also look for two miners skilled in digging and raising ore. As a result, Cornish miners hired by the company began work at the mine.[14] |

| LABOR DISPUTE |

|

Benjamin Grayson, a merchant at Dumfries, VA, was the manager of the mine. He had labor difficulties with miners who complained of a lack of an adequate supply of meat and too few holidays.[15] It was the miners’ opinion that they were entitled to time off on Saturday afternoons and for red letter days, which refers to holidays.[16] Four of the miners wrote to Carter expressing their complaints. Carter, upon receiving the letter and learning that the miners had taken themselves to a tippling house[17] south of the Occoquan river where they got drunk for several days, provided Grayson with the miners’ indenture papers so Grayson could discuss the terms of the indentures with the miners.[18] In keeping with “act first, ask questions later,” Carter sent the miners papers stipulating that Grayson was the master of the miners, and as such, could act in Carter’s stead to discipline them.[19] Carter later wrote to his agent to inquire if miners were typically given time off for holidays.[20] It was Carter’s belief that providing the miners with good milk, homony,

& milk & mush should content them during the summer months. He

argued that this is the same fare as other Virginians who work harder and have

no meat. Carter expected the miners to make their provisions last longer.[21]

He later stated that the miners received plenty of salt meat and that several

venison had been killed for them.[22] Carter asked Grayson to keep a detailed ledger of the miners work hours so that it would be evident whose wages should be docked for not working Saturday afternoons or holidays. Carter was particularly displeased with two of the miners, Hawies and Brunton,who were picked up in the streets of London in want of bread and common necessaries and signed on as indentured servants.[23] Some of the Bristol miners said that Hawies was previously a sailor on a Man of War and served for several years in Maryland as an indentured farm laborer rather than a miner. Their opinion of Hawies was that he was an indifferent worker.[24] |

| COPPER VEIN DISCOVERED |

|

In all, the miners raised at least four tons of ore out of this vein before it played out. Ore with less copper content was in the last barrels. Carter had a small furnace in which he assayed several of the later barrels of ore which yielded 1/3rd copper.[27] |

| SEARCH FOR ANOTHER VEIN |

|

By September 1731, the rich vein had run out. The miners drove deeper into the earth and carried drifts out to all points of the compass. Some of the miners wanted to dig new shafts some distance away, but they couldn’t agree where. However, Carter was resolute in sinking deeper into those shafts where the veins of the rich ore were met with water. In May 1732 three months before his death, Carter wrote that all hopes for more ore had entirely vanished, not having found more copper since the vein they found the prior summer, though they had been looking ever since.[28]

|

| ENDNOTES |

|

[1] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Indenture among Robert Carter, Robert Carter, Junior, Charles Carter, John Carter, and Judith Page, 05 November 1731, as viewed online at http://carter.lib.virginia.edu/indexltrs.html [2] Northern Neck Grant B:145, 14 October 1728, as viewed online, Library of Virginia, Land Office Grants. [3] Joseph P. Smoot and Gilpin R. Robinson, Jr., Base- and precious metal occurrences un the Culpeper basin, northern Virginia, Department of the Interior U.S. Geological Survey, Early Mesozoic Basins Workshop, 1987; Also, G. R. Robinson, Jr., Base- and Precious Metal Mineralization Associated with igneous and Thermally Altered Rocks in the Newark, Gettysburg, and Culpeper Early Mesozoic Basins of New Jersey, Pennsylvania, and Virginia, in W. Manspeizer, Ed., Triassic-Jurassic Rifting, New York, 1988, p. 640. [4] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to James Bradley, 09 September 1729. [5] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Edward Athawes, 16 April 1730. [6] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Edward Athawes, 22 Jul 1731. [7] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Edward Athawes, 16 April 1730. Note: The Virginia General Assembly set the size of a tar barrel in 1705 to be large enough to contain 31.5 gallons, Winchester measure. Acts of Assembly, Passed in the Colony of Virginia: From 1662, to 1715, Volume 1, John Basket, Printer, London, 1727, p. 231, as viewed on Google Books. [8] Escheat land is previously granted land that reverted to the Northern Neck Proprietary because the terms of the grant were not met. That land was then available to be granted to someone else. [9] Northern Neck Grant C:39, 02 March 1729, as viewed online, Library of Virginia, Land Office Grants. [10] Northern Neck Grant C:38, 01 March 1729, as viewed online, Library of Virginia, Land Office Grants. Note: The intersection of Popes Head Road and Ox Road (Rt 123) is located on this tract of land. [11] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Indenture between Robert Carter of Carotoman, Robert Carter, younger, of Nominii, Charles Carter of Urbanni, John Carter of Shirley of behalf of the sons of Mann Page, and Judith Page, widow of Mann Page, 04 Nov 1731. [12] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Edward Athawes, 16 April 1730. [13] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Edward Athawes, 16 April 1730. [14] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to James Bradley, 15 May 1730. [15] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Benjamin Grayson, 13 Jul 1731. [16] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Edward Athawes, 22 Jul 1731. [17] A tippling house is a place where liquor was sold by the glass. [18] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Edward Athawes, 22 Jul 1731. [19] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Benjamin Grayson, 13 Jul 1731. [20] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Edward Athawes, 22 Jul 1731. [21] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Benjamin Grayson, 13 Jul 1731. [22] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Edward Athawes, 22 Jul 1731. [23] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Benjamin Grayson, 13 Jul 1731. [24] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Edward Athawes, 22 Jul 1731. [25] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to William Dawkins and Edward Athawes, 26 Jul 1731, Also Letter from Robert Carter to Benjamin Grayson, 27 Jul 1731. [26] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Benjamin Grayson, 27 Jul 1731. [27] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to Edward Athawes, 10 Sep 1731. [28] Edmund Berkeley, Jr., ed., The Diary, Correspondence, and Papers of Robert “King” Carter of Virginia 1701-1732, Letters, Letter from Robert Carter to William Dawkins, 12 May 1732. |

| Home |

|

| © Debbie Robison, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved. |

Robert “King” Carter, his sons Robert and Charles Carter,

and son-in-law Mann Page formed a company in 1728 to mine copper from an area

near present-day Dulles Airport.

Robert “King” Carter, his sons Robert and Charles Carter,

and son-in-law Mann Page formed a company in 1728 to mine copper from an area

near present-day Dulles Airport.

It wasn’t long before Carter’s disappointment over the labor

dispute was softened, for soon thereafter, the miners discovered a large vein

of copper ore. One day, Carter was lamenting that the miners were blowing up

the rocks and trying to persuade him that they will find ore soon, and the next

day he happily received samples of ore from a very rich vein.

It wasn’t long before Carter’s disappointment over the labor

dispute was softened, for soon thereafter, the miners discovered a large vein

of copper ore. One day, Carter was lamenting that the miners were blowing up

the rocks and trying to persuade him that they will find ore soon, and the next

day he happily received samples of ore from a very rich vein.