| Little River Turnpike Constructed 1802-11 |

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

by Debbie Robison September 10, 2017 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In order to improve travel for farmers who conveyed their goods from the western counties to the port of Alexandria, the Little River Turnpike was constructed of gravel from Alexandria to the ford of Little River near present-day Aldie, Virginia. The road, almost 34 miles in length, was constructed using slave labor, which involved clearing the proposed route of trees and vegetation, quarrying gravel, and crushing stone. Construction, which began in 1802 in Alexandria, was completed nine years later at Little River in 1811. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| FIRST AMERICAN TURNPIKES WERE IN NORTHERN VIRGINIA | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Before there

were turnpike roads, local citizens were required to keep roads in good

condition. The court assigned sections of roads to men who lived along the

route, and if you didn’t maintain your section, you could be fined by the

court. [1] Some roads

were more heavily traveled than others due to large quantities of produce and

grains being conveyed in wagons along main roads from the western counties to ports

of navigation, such as Alexandria. Foreign goods were conveyed back in the

reverse direction from the port westward. The men who lived along the main

roads felt that the method of keeping the roads in repair resulted in their

having an unequal burden so they petitioned the legislature to create toll

roads so that the people who benefit from the road pay for its upkeep.[2]

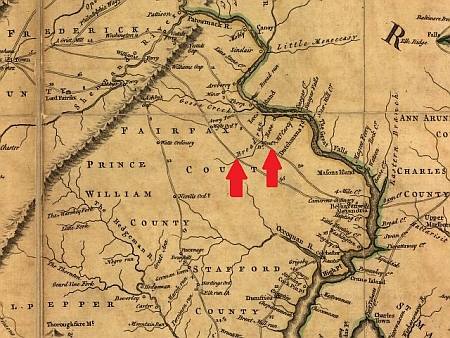

Route of First Turnpike Roads in America, depicted on map of Virginia drawn by Peter Jefferson and Joshua Fry, 1751, Courtesy Library of Congress

As a result, the Virginia General Assembly passed “An Act for Keeping Certain Roads in Repair” in 1785 that levied tolls on two existing roads in northern Virginia.[3] This is significant. This act created the first American turnpikes. One of these roads, known as “The Road from Alexandria to Winchester,” took the route of present day Braddock Road in Fairfax County and Snickersville Turnpike in Loudoun County for much of its length. The other road, known as the “Main Road” or “Great Road,” generally took the route of present day Route 7. Toll gates were constructed and the toll money was used by appointed commissioners to repair the highways. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| FAIRFAX AND LOUDOUN TURNPIKE ROAD COMPANY | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

While tolls and other taxes succeeded in removing the burden of repair from men living along the routes, the roads continued to be inadequate. In 1795, inhabitants of Loudoun County petitioned the legislature for an act to incorporate a company to build a road from Little River to Alexandria. They wanted a road made of stone and gravel in order to keep the wheels of carriages from cutting into the soil.[4] The road would begin at the place where Little River was crossed by the existing turnpike. An act was passed the same year that formed the Fairfax and Loudoun Turnpike Road Company. The company was empowered to sell stocks to subscribers in order to raise funds to build the road. Dividends would be paid using excess toll revenue not used for road repairs. Richard Bland Lee, of Sully, was one of the commissioners appointed by the act to oversee the turnpike company.[5] The Fairfax and Loudoun Turnpike Company was not a success. The act required road construction to begin within two years and be completed within seven years or the road would revert to the Commonwealth. Unfortunately, there were not enough subscribers purchasing stock in the company to commence with road construction. Most of the subscribers resided in Alexandria. Landowners west of Goose Creek, who pinned their hopes on navigation down the Shenandoah and Potomac Rivers, didn’t subscribe. And landowners closer to Alexandria didn’t subscribe if they learned the turnpike wouldn’t pass directly through their own land.[6] After citizens complained that the road was a great grievance and the law by which the turnpike road was regulated was inadequate, the Virginia General Assembly passed an act in 1802 creating the Little River Turnpike Company.[7] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| LITTLE RIVER TURNPIKE: DECIDING ON THE ROUTE | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

The act stipulated that the road extend from the intersection of Duke Street with the south-west line of the District of Columbia (near the present-day intersection of Duke Street and Dangerfield Road in Alexandria) to the ford of Little River. It also required the company to take into consideration the shortness of distance and the nature of the ground.[8] The route between the start and end points was up for debate. This was not a new discussion. Francis Peyton prepared a survey of the proposed Fairfax and Loudoun Turnpike whereby the route followed a straight line from Little River to Alexandria. There would have been construction challenges with this route had it been built, including having to cut through the cliffs of Difficult Run and through the enormous hills of Ravensworth, a large tract of land east of Difficult Run.[9] The commissioners of the Little River Turnpike Company were divided on the route. Two commissioners wanted the turnpike to pass through Centreville using the existing road; however, they were out-voted by three commissioners who were in favor of the road passing by Fairfax Court House as designated in a survey by Simon Summers. The road would then continue in a straight line to the ford of Little River. This route, the winning side argued, was shorter and less costly. [10] Much of the route passed through Ravensworth. Nicholas and Giles Fitzhugh, who inherited large parcels of the Ravensworth tract, agreed that the turnpike could extend straight through their land without having to follow their property boundaries.[11] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| FUNDING CONSTRUCTION | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Construction of the turnpike was funded by subscribers who purchased stocks valued at $100 each. Ten dollars was paid up front and the balance was to be paid out of dividends.[12] However, as it turned out, the stockholders were called upon to pay another ten dollars after one year.[13] The Commonwealth of Virginia provided some of the funding for the initial construction by purchasing at least 42 shares in March 1805.[14] In 1832 there were 126 stockholders; those with the largest number of shares were as follows.[15]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| CONSTRUCTION | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Construction began in October 1802 starting at Alexandria.[16] The law required that the road be constructed 30 feet wide with a sufficient ditch on each side. Twenty feet of the width had to be covered with gravel or stone, but only in areas that required it. By 1807, the Company was clearing a 56-foot wide road with a convex form that was 20 feet in width. The convex center was paved with broken stone that could pass through a 2.5” ring. The gravel was 9” deep on firm ground and 12” deep on the moist sections of the road.[17] Stone was obtained from nearby land and picks and hammers were used to break the stone. In 1826, the company purchased a riddling machine to pass the gravel through a sieve.[18] Beginning in 1828, the Company adopted the McAdam plan for making pavement repairs and for replacing miles of pavement. This plan, developed by Scottish engineer John Loudon McAdam, stipulated that the top layer of stones consist of smaller compacted gravel that sloped away from the center of the road.[19]

Original section of the Little River Turnpike near the Annandale NOVA campus, now a side street after road realignment.

The Company could enter nearby property to look for stone beds or gravel and purchase needed materials based on a price determined by three disinterested landowners. Property owners received payment for the purchase of the land required for the road, as well as for additional fencing that might have been necessary. [20] By Christmas Eve 1803, about four miles of the road had been built, though only three miles were paved with gravel.[21] The four-mile mark was around present-day Landmark Mall. Male African American slaves built the turnpike. Richard Ratcliffe, construction superintendent beginning in December 1803, hired twenty slaves on a yearly contract as laborers.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

In 1804, Ratcliffe posted a ten-dollar reward for Gabriel, a slave about 21 years old, who escaped from bondage while working on the turnpike.[23] In 1805, Jacob, a 50-year-old slave who was working on the road, fled from the turnpike. A ten-dollar reward for his return was posted by the Little River Turnpike Company.[24] Ratcliffe continued to use slave labor to construct in turnpike in 1808 when he placed another advertisement for twenty able bodied Negro Men.[25] In 1804, Ratcliffe finished graveling the first four miles, built an additional two miles of gravel road, and grubbed up all of the timber in the new road, except for the largest trees, for more than half the distance to Little River.[26] The first ten miles were completed in October 1806, including constructing a bridge over Accotink Run. Once ten miles of the road was established, the company could have it viewed by persons appointed by the Governor of Virginia. If the work was acceptable, tolls could be collected on that stretch of road. Two toll gates were constructed on the first ten miles and gate keepers began collecting tolls.[27] The entire length of the Little River Turnpike, just shy of 34 miles, was completed in December 1811. [28] Once the road was examined in January 1812 and approved, the company erected the final two toll gates. After the road was completed, the turnpike company worked to keep the road in repair and to make improvements. Wooden bridges that were originally constructed were replaced with stone bridges and hills that were too steep were cut down.[29] From 1802 through 1817, the cost of making and keeping the turnpike in repair was $213,928.74.[30] A stone bridge was constructed over Accotink in 1823. It had two arches, one with a 24-foot span and the other with a 12-foot span. This turned out to be insufficient to withstand the summer flood of 1824. The bridge had to be rebuilt, this time incorporating an additional arch with an 18-foot span, side walls, and four-foot thick abutments and piers. It cost the company $900.[31]

In 1826, a new stone bridge was built over Little River at the joint expense of the Little River Turnpike Company and the Ashby’s Gap Turnpike Company.[32] This bridge still exists and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Stone Bridge at Aldie, Virginia | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TOLLS | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Funding for the road was received by collecting tolls. The toll originally established for every ten miles of road was based on the quantity of goods taken to market. Some portions of the turnpike were more difficult to pave due to streams and terrain so the turnpike directors petitioned the Virginia General Assembly to receive tolls once 5 miles of the most impossible parts were paved. In order to encourage the use of wider wheels, which didn’t cut up the road as much as narrow wheels, the toll was reduced the greater the wheel width. Return wagons weighing 500 lbs. or less did not have to pay a toll.

The company printed tickets, which were handed out at the gates.[33] Occasionally the gate keepers received counterfeit bank notes, which the company wrote off as a loss.[34] For the most part, revenue increased until the Panic of 1819 and subsequent depression caused a reduction in traffic along the turnpike.[35]

Total annual toll revenues per year. A portion of the tolls in 1811 were retained by the superintendent for road repairs. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| TOLL GATES | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

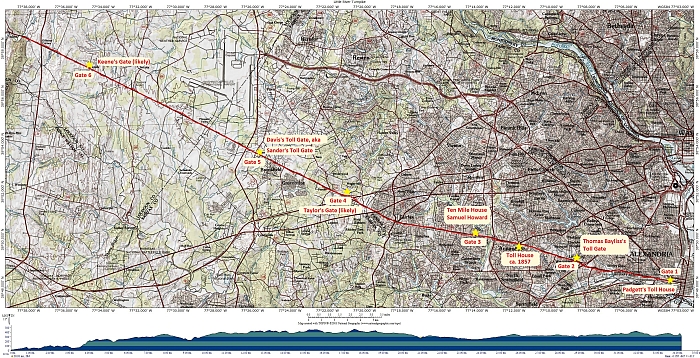

Initially there were seven toll gates, which were opened on the following dates: Gate 1 – October 11, 1806 Gate 2 – October 11, 1806 Gate 3 – February 1, 1809 Gate 4 – February 1, 1809 Gate 5 – January 15, 1810 Gate 6 – 1812 Gate 7 – 1812

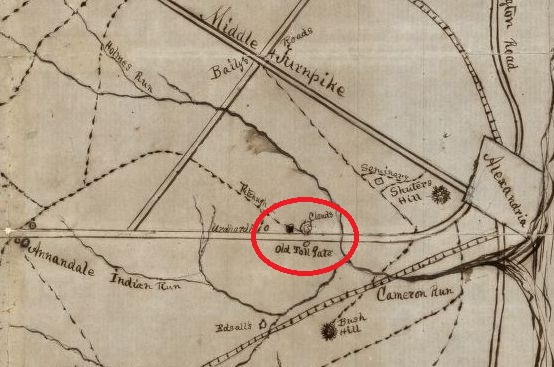

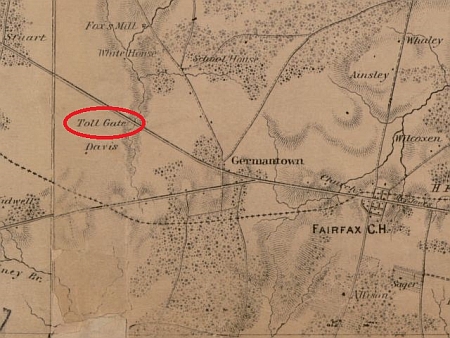

Locations of Toll Gates on the Little River Turnpike A larger version of this map is available in Adobe pdf format. The toll gates were spaced at intervals along the turnpike. The first gate was located at the beginning of the turnpike near the District of Columbia (Alexandria) line. A toll house was constructed at the gate. It became known as Padgett’s Toll House, after George H. Padgett who operated the gate for many years until the commencement of the Civil War.[36] The second gate, located near present day Lincolnia, was operated by Thomas Bayliss. As a man long known as the toll keeper for Little River Turnpike, he became well-known in the area. He died at age 99 in 1876.[37]

Location of Gate #2 shown on Civil War Field Map, 1862, Courtesy Library of Congress Gate number three was located on the turnpike at the Ten Mile House across from the present-day Annandale campus of the Northern Virginia Community College. The Ten Mile House, adjacent to William Gooding’s Tavern, was operated by Samuel Howard, Gooding’s son-in-law. Farmers with wagons loaded with wool had the option of depositing the wool at Howard’s toll house. Howard had an arrangement with James Kidwell who operated a wool carding mill nearby on Accotink Creek. Howard accepted wool shipments that were then conveyed to the carding machines and rolls and when ready, returned to the toll house for farmers to pick up.[38] Location of Gate #3 shown on 1937 USDA aerial photo, Image Courtsey Fairfax County Park Authority, NOTE: It is unknown if the toll house still existed in 1937; however, this was the location for both the toll house and the Gooding Tavern. The fourth gate was located at the Little River Turnpike bridge over Difficult Run. This may have been the gate that was operated by Sanford Taylor in 1852.[39]

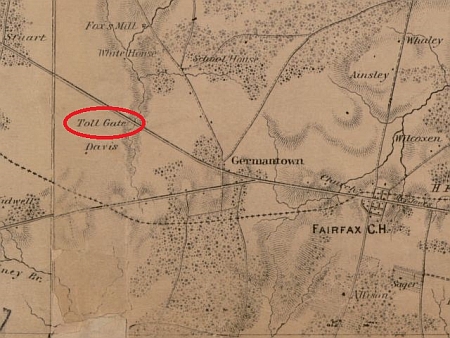

Location of Gate #4 shown on Map of Northeastern Virginia and Vicinity, 1862, Courtesy Library of Congress Gate number five was located near Chantilly at the intersection with Centreville Road. James Davis was the toll keeper for many years before the Civil War.[40] The gate was known as Sanders Tollgate during the war.

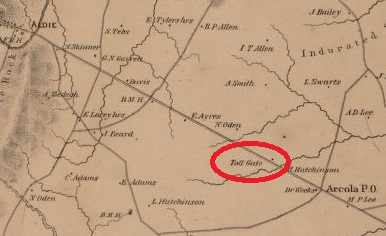

Location of Gate #5 shown on Map of Northeastern Virginia and Vicinity, 1862, Courtesy Library of Congress Gate 6 was located in Loudoun County at Lenah. This may have been the gate that was operated by John Keene in 1852.[41] Stephen Beard also operated a tollgate on the turnpike about three miles east of Aldie.[42] He ran a wagon stand there, similar to a tavern, where teamsters driving wagon teams could put up for the night. When Beard died 1844 his land where the toll house was located was sold so the turnpike directors purchase two acres of land nearby and built a new toll house, possibly for a toll house at Lenah.[43]

Location of Gate #6 shown on Map of Northeastern Virginia and Vicinity, 1862, Courtesy Library of Congress The location of the seventh gate is unknown, but it may have been located at the western end of the turnpike near Little River. By 1852, there were only six toll gates in operation.[44] In 1857, the Little River Turnpike purchased 2.75 acres at Annandale where they constructed a new toll house on the south side of the turnpike just east of present-day Ravensworth Road.[45] | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| END OF TOLL COLLECTION | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

Collection of tolls continued until an Act of the Virginia General Assembly transferred ownership of the road from the Little River Turnpike Company to the Fairfax County Board of Supervisors in 1896 with one exception.[46] During the Civil War, from 1861-1864, the Union Army threw open the toll gates and no tolls were collected.[47]

End Notes [1] Beth Mitchell, Fairfax County Road Orders 1749-1800, June 2003, as viewed online at http://www.virginiadot.org/vtrc/main/online_reports/pdf/03-r19.pdf [2] Legislative Petition, Freeholders & Inhabitants: Petition, Roads/Turnpike Companies, October 13, 1792, Library of Virginia, as viewed at http://www.virginiamemory.com/collections/petitions [3] Hening’s Statutes, Laws of Virginia 1785, pp. 75-81. [4] Legislative Petition, Inhabitants: Petition, Charters/Incorporations, Roads/Turnpike Companies, November 13, 1795, Library of Virginia, as viewed at http://www.virginiamemory.com/collections/petitions [5] Samuel Shepherd, The statutes at large of Virginia : from October session 1792, to December session 1906 [i.e. 1807], inclusive, in three volumes, (new series,) being a continuation of Hening …, Volume I, December 26, 1795, pp, 378-388, as viewed at https://babel.hathitrust.org/cgi/pt?id=mdp.35112104867306;view=1up;seq=384 [6] “To the Stockholders in the Little River Turnpike Company,” Alexandria Daily Advertiser, November 17, 1803, p. 2. [7] The statutes at large of Virginia : from October session 1792, to December session 1906 [i.e. 1807], inclusive, in three volumes, (new series,) being a continuation of Hening ... Volume II, pp 383-386, as viewed at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009732153; Also Legislative Petition, “Ask for an alteration in the law respecting roads so as to keep them in repair,” December 8, 1800, Library of Virginia, as viewed at http://www.virginiamemory.com/collections/petitions [8] The statutes at large of Virginia : from October session 1792, to December session 1906 [i.e. 1807], inclusive, in three volumes, (new series,) being a continuation of Hening ... Volume II, pp 383-386, as viewed at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009732153; [9] “To the Little River Turnpike Company,” Alexandria Expositor, September 5, 1803, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com [10] The statutes at large of Virginia : from October session 1792, to December session 1906 [i.e. 1807], inclusive, in three volumes, (new series,) being a continuation of Hening ... Volume II, pp 383-386, as viewed at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009732153; Also, Leven Powell, Alexandria Daily Advertiser, November 30, 1803, p. 3, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com [11] Alexandria Daily Advertiser, November 19, 1803, p. 3, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com [12] William Hartshone, “Subscriptions for the turnpike road,” Times and District of Columbia Advertiser (Alexandria), p. 1, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com [13] William Hartshorne, “Little River Turnpike Company,” Alexandria Expositor, p. 1, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com [14] Little River Turnpike Company Stock Certificates, March 1805, Virginia Board of Public Works, Library of Virginia, Richmond. [15] Little River Turnpike Company List of Stockholders, 1832, Virginia Board of Public Works, Library of Virginia, Richmond. [16] Alexandria Daily Advertiser, December 10, 1804, p. 3, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com [17] “Notice is Hereby Given,” Alexandria Daily Advertiser, December 23, 1807, p. 1, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com [18] Little River Turnpike Company Report, 1826, Virginia Board of Public Works, Library of Virginia, Richmond. [19] Little River Turnpike Annual Report 1829, Board of Public Works Collection (Little River Turnpike Folder), Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia. Also mentioned in the 1830-1832 annual reports. [20] The statutes at large of Virginia : from October session 1792, to December session 1906 [i.e. 1807], inclusive, in three volumes, (new series,) being a continuation of Hening ... Volume II, pp 383-386, as viewed at https://catalog.hathitrust.org/Record/009732153; [21] Alexandria Daily Advertiser, December 10, 1804, p. 3, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com [22] Richard Ratcliff, “Wanted to Hire,” Alexandria Daily Advertiser, December 28, 1803, p. 3, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com; Also, R. Ratcliffe, “Notice,” Alexandria Daily Advertiser, January 19, 1808, p. 1, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com [23] Richard Ratcliffe, “Ten Dollars Reward,” Alexandria Daily Advertiser, August 2, 1804, p. 4, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com [24] Joseph Powell, “Ten Dollars,” Alexandria Advertiser, October 29, 1805, p. 1. [25] “Notice,” Alexandria Daily Advertiser, January 19, 1808, p. 1. [26] Alexandria Daily Advertiser, December 10, 1804, p. 3, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com [27] “Little River Turnpike Road,” Alexandria Daily Advertiser, December 22, 1806, p. 2, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com; Also, “Little River Turnpike Road,” Alexandria Daily Advertiser, November 12, 1806, p. 4, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com [28] Josiah Thompson’s Report of the Little River Turnpike Company, November 1817, Library of Virginia, Board of Public Works Collection. Also, Alexandria Advertiser, December 22, 1806, p. 2. [29] Little River Turnpike Company Report, 1818-1822, Virginia Board of Public Works, Library of Virginia, Richmond. Additional reports describe other repairs and construction of bridges. [30] Little River Turnpike Company Report, 1817, Virginia Board of Public Works, Library of Virginia, Richmond. [31] Little River Turnpike Company Report, 1823, 1824, Virginia Board of Public Works, Library of Virginia, Richmond. [32] Little River Turnpike Company Report, 1826, Virginia Board of Public Works, Library of Virginia, Richmond. [33] Little River Turnpike Company Report, January 1821, Virginia Board of Public Works, Library of Virginia, Richmond. [34] Little River Turnpike Company Report, December 1821, December 1823, Virginia Board of Public Works, Library of Virginia, Richmond. [35] Little River Turnpike Company Reports, 1806-1826, Virginia Board of Public Works, Library of Virginia, Richmond. [36] “Death of an Old Citizen,” Alexandria Gazette, September 22, 1866, p. 3. as viewed at www.genealogybank.com Obituary of Capt. George H Padgett who operated the toll gate for a number of years prior to the commencement of the war. [37] “A Good Citizen Gone,” Evening Star, February 26, 1876, p. 4, col. 5, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com. Obituary of Thomas Bayliss. [38] “Wood Carding,” Alexandria Gazette, June 25, 1840, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com. [39] Little River Turnpike Annual Report 1852, Board of Public Works Collection (Little River Turnpike Folder), Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia. [40] Little River Turnpike Annual Report 1852, Board of Public Works Collection (Little River Turnpike Folder), Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia; Also, “Public Sale,” Alexandria Gazette, July 14, 1847, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com. [41] Little River Turnpike Annual Report 1852, Board of Public Works Collection (Little River Turnpike Folder), Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia. [42] “Public Sale of Land,” Alexandria Gazette, December 4, 1844, p. 2, as viewed at www.genealogybank.com. [43] Little River Turnpike Annual Report 1845, Board of Public Works Collection (Little River Turnpike Folder), Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia. [44] Little River Turnpike Annual Report 1852, Board of Public Works Collection (Little River Turnpike Folder), Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia. [45] Fairfax County Deed Book Z3(78)124, September 14, 1857. [46] Fairfax County Board of Supervisors Minutes, May 21, 1896, p. 318, microfilm, Fairfax County Public Library, Virginia Room, Fairfax. [47] Fairfax County Court Order Book 1863, p. 330, February 20, 1866, Fairfax Circuit Court Archives, Fairfax, Virginia. | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Home |

|

| © Debbie Robison, unless otherwise noted. All rights reserved. |