| Formation and Development of the Town of Matildaville, Virginia |

|

by Debbie Robison August 11, 2011 |

|

The former town of Matildaville was located on land within present-day Great Falls Park Virginia. While only ruins remain of the structures that were built in the town, these traces of the past provide a link back in time to the country's early struggles to build a skirting canal around the Great Falls. The canal was part of a larger project conceived by George Washington to provide an avenue of transportation for goods from the country's interior to ports at Georgetown and Alexandria. Washington was the first president of the Potowmack Company, which was formed to construct the canal.

The town of Matildaville was authorized by the Virginia General Assembly in 1790 on 40 acres of land belonging to Bryan Fairfax. The town would be located adjacent to a strip of land along the Potomac River at Great Falls condemned for use by the Potowmack Company (later Potomac Company). The trustees of the new town were to have the town laid off into 1/2 acre lots with convenient streets.[1]

Great Falls, Virginia

George Washington had foreseen placement of the town at the canal near the basin where boats awaited their turn through the locks. In February 1789 he wrote to Thomas Jefferson regarding his thoughts on the matter.

...From the conveniency of the basin a little above the spot where the locks are to be placed, and from the inducements which will be superadded by several fine mill-seats, I cannot entertain a doubt of the establishment of a town in that place. Indeed, mercantile people are desirous that the event should take place as soon as possible. Manufactures of various commodities, and in iron particularly, will doubtless be carried on to advantage there. The mill-seats I know have long been considered as very valuable ones. How far buildings erected upon them may be exposed to injuries from freshets or the breaking up of the ice, I am not competent to determine from my own knowledge; but the opinion of persons better acquainted with these matters than I am, is, that they may be rendered secure... [2]

General Henry Lee was a proponent of the town and was a member of the Virginia General Assembly when the act to establish the town was passed.[3] It is generally accepted that the town was named after his first wife, Matilda Lee, who died months before passage of the act.[4] John Davis, a traveler to the falls in 1802 noted in his journal that the town was named after General Lee's wife.[5] A fanciful alternate theory, reported in 1911, asserted that legend purported that Matilda was a stolen bride who in colonial times was hidden on Cupid's Bower, an island below the falls.[6] During a time when the Potomac Canal operated, the falls also carried Matilda Lee's name and were known as Matilda Falls.[7] Lee was governor of Virginia from 1791-1794, during which time he entered into an agreement to lease from Bryan Fairfax a large tract of land surrounding the town of Matildaville for 900 years.[8] Lee's agent, Roger West, purchased 30 lots in the town of Matildaville on behalf of Lee; however, few if any of these lots were ever sold.[9]

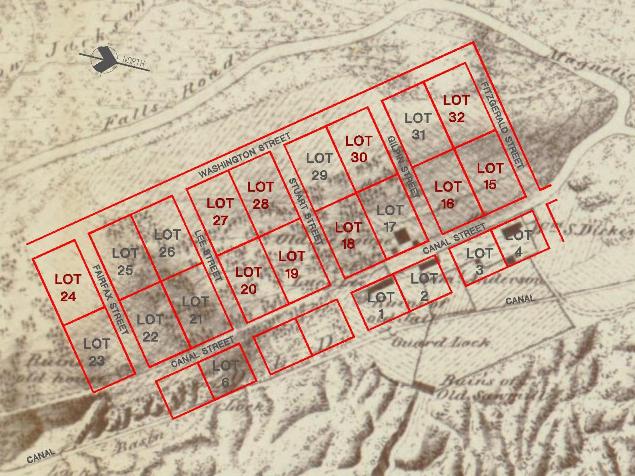

A plat of the town would have been created by the trustees; however, there is no known plat of the town of Matildaville in existence today. Following is a sketch of how a portion of the town may have been laid out. This conceptual plan, overlaid on top of an 1866 survey map, is based on descriptions provided in deeds. The lots are 117' wide and either 105' deep or 187.5' deep depending upon location. The streets are assumed to be 40' wide, the same width designed for the streets in Centreville, VA which was created in 1792. The street names included Canal Street, Washington Street, Fitzgerald Street, Gilpin Street, Stuart Street, Lee Street, and Fairfax Street. Lot numbers shown in dark grey indicate lots that were eventually sold. There was no evidence found that lots shown with numbers in red were ever sold. The red lot numbers are a guess based on the location of the known lots.

Conceptual Plat of the Town of Matildaville, VA

The background map was prepared in 1866 by J. De la Camp and is titled A Topographical map of the Estate of Great Falls Manufacturing Company, Fairfax Co., Va.[10] The Great Falls Manufacturing Company purchased the land at the falls in 1851.[11]

The trustees advertised the sale of several lots of land in the town to be held at a public auction in July 1795. Purchasers were required to build a dwelling house at least 16 feet square with a stone or brick chimney within five years of purchase. If the house wasn't built within that time, the trustees could resell the lot. As a result of the public auction, Joseph Gilpin purchased lot 31. [12] It is unknown if other lots were sold as a result of this auction since some lots were purchased at various times but not recorded in the county deed books. In 1797, Tobias Lear, a director of the Potowmack Company, purchased seven lots numbered 6, 17, 21, 22, 25, 26, and 29.[13] Many of these lots were left vacant; however, town trustees probably didn't bother reselling them since they couldn't unload most of the other town lots anyway. In total, exclusive of Henry Lee's investment in 30 lots, there were about 12 lots sold in the town of Matildaville, at least half of which had some type of structure and approximately five of which had buildings large enough to be assessed a tax.[14]

|

| Lot 1: Superintendant's House and Boarding House |

Lot 1 was owned by the Potomack Company. In addition to land needed for construction of the canal, ownership of Lot 1 in the town of Matildaville was transferred to the Potomack Company through condemnation proceedings.[15] A house for the canal superintendant and a workers boarding house were constructed on this lot.

Superintendant's House Ruin

In February 1796, Captain Christopher Myers was offered the position of engineer and superintendant of the works at the canal. The following month, the company directors resolved to complete the house on the lot belonging to the company and to erect other lodging necessary to accommodate the workers. The superintendant's house, which was to be a two-story house of stone and brick, was to measure 25 feet in the front and be 35 feet deep. The dimensions specified for the building to lodge the hands was 72 feet long by 18 feet wide, 7 feet high in the clear, and covered with plank.[16]

Since the Potomac Company only owned Lot 1 at this time, both buildings had to have been constructed on this lot. A Topographical map of the Estate of Great Falls Manufacturing, Fairfax Co., Va. depicts these two buildings adjoining each other. The structure extended across almost the entire width of the lot.

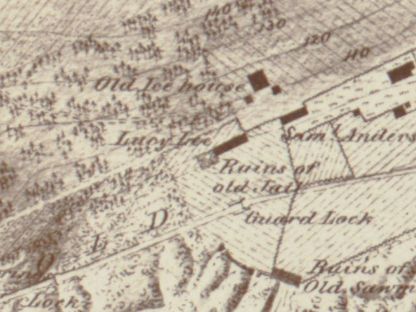

Structures labeled Lucy Lee and Ruins of old Jail indicate the workers' lodging house and superintendant's house, respectively.

1866 Map Showing Lot 1

The lodging house must have been completed soon after the directors resolved to have it finished. In June 1796, the superintendant advertised for workers and offered good quarters.

NOTICE For the employment of Stone-cutters & Hands. The President and Board of Directors of the Potomac Company having authorized me to engage a number of hands, wanted for their works, I give this public notice to any persons inclined to enter on their works, that they shall have LIBERAL WAGES, SOUND RATIONS and good QUARTERS, and every condition of agreement punctually fulfilled. Preference will be given to quarry laborers, and men accustomed to the blasting of stone. Such persons as are disposed to hire out their servants by the quarter, half year or year, will meet with generous encouragement by application to me at the city of Washington, or at the Great Falls of Potomac. CHRISTOPHER MYERS, Engineer to the Potomac Company. N.B. Stone-cuters will meet with constant employ, with sheds and lodging-room, by applying as above. June 24. [17]

In 1798 the Potomac Company employed at least five white men over the age of 16 and six African-American men over the age of 16 who were living at the canal.[18]

Christopher Myers resigned his position after having a dispute with the company.[19] He died not long thereafter in 1798.[20] His widow, Jane Myers, was encouraged by the company directors and others to open a tavern in the superintendent's house.

Mrs. Jane Myers, widow of the late Capt. Christopher Myers, formerly engineer to the Potomak Company, being encouraged by the Directors, and a number of her husband's friends, to open a TAVERN in the house occupied by him at the Great Falls, beg leave to offer her services to them and the public in general. She flatters herself that her desire to please those that may call at her house, with having employed proper assistants, will ensure to her that support which an undertaking of that kind requires. She intends to open a tavern the second week in September. 24th - August, 1799. [21]

John Davis, a well-known traveler through the United States, was accommodated with a supper and a bed by the Widow Myers, a Methodist, while he visited the falls in 1802.[22]

By 1845, the boarding house was operated by Miss Lucy Lee, affectionately called Aunt Lucy.[23] She was a free-born woman of mixed race who was well respected and a long time resident of the place.[24] It was likely her boarding house that was described in an 1845 newspaper article about a visit to the falls. The author was not impressed with the lodging house.

On the Maryland side there is one very indifferent tavern; and on the Virginia side the chief resort is the cabin of a colored woman, who lends her floor for the cotillions and cooks the viands of the (often) numerous parties who flock to the Falls. She is clean and civil, owns six modern and one very venerable arm chair, and inhabits a ruined house, which, if not speedily propped, will one day fall on the head of her guests.[25]

Lucy Lee was operating the boarding house when it was owned by the Great Falls Manufacturing Company. The company superintendant, Mr. Hurst, boarded with her.[26] In 1873, it was reported that fishermen and tourists visiting the falls stayed at her lodging.[27]

|

| Lot 2: Joseph Gilpin House |

Gilpin House Ruin

Lot 2 was leased by George Gilpin from Henry Lee in 1793. By then Gilpin had already improved the lot, probably by constructing a house.[28] In 1797 this structure was assessed the highest tax value, based on potential rental income, of any house in town except for a building constructed on Lot 4 that had an equal value.[29] A note on a deed records that George Gilpin paid Henry Lee 16 years of rent for this lot commencing on December 26, 1809 and was thereafter discharged for paying any further rent. [30]

Joseph Gilpin likely lived in the house since it is recorded that he was a resident of the town of Matildaville.[31] Joseph, who paid the taxes on the lot, was the son of George Gilpin, a director of the Potomac Company and town trustee.[32] Joseph Gilpin may have operated a store from this building. In 1798 and 1799 he purchased store licenses to sell foreign retail goods.[33]

The ruin visible today suggests that the house had a stone foundation and a brick chimney.

Around 1814, the lot was purchased by John James.[34] It is unknown how John James used the house, whether as a residence or an income producing property. In 1823 the house had an assessed value of $200 compared to the value of the tavern on Lot 4 that had an assessed value of $300.[35] Improvements were made to the house resulting in an increase in the assessed value in 1824 up to $300. The improvements were noted in the tax ledger and typically indicate that an addition was made to the building.[36]

After John James's death, his heirs sold the house to James Campbell in 1825.[37] By 1860 it was rented to Samuel Anderson, a carpenter. He was still living in this house in 1866 when the Great Falls Manufacturing Company map was prepared. Samuel Anderson married Jane E. Dickey, who grew up in the tavern on Lot 4.

1866 Map Showing Lot 2

Lot 2 was purchased in 1868 by John Powell after Campbell did not pay the taxes on the property.[38] Powell turned around and sold the lot to the Great Falls Manufacturing Company the following year.[39]

|

| Lot 3: Springhouse |

Springhouse Ruin

Roger West purchased Lot 3 from the trustees of the town of Matildaville in July 1797 for 100 pounds, the highest known priced paid for any unimproved lot in the town of Matildaville.[40] Several other lots sold for about 20 pounds. This higher price may reflect the added value of having a spring on the lot.

In 1798, Tobias Lear, a director of the Potomac Company, purchased lot 3 from Roger West. The purchase was for his personal investment; he did not transfer ownership of the lot to the Potomac Company. The increased purchase price of 150 pounds may suggest that a structure was already constructed on the lot by Roger West.[41] It is possible that only a springhouse was constructed on the lot, though the lot was assessed an annual rental value of 30 pounds in 1797. By 1820, the first year buildings were valued, Lear owned six lots in the town of Matildaville. Five of these lots were unimproved. His improved lot was likely Lot 17. Lear's heirs owned Lot 3 until at least 1866. [42]

A newspaper photo of a springhouse in 1917, whose rock walls bear some resemblance to the rocks of the ruin today, suggests that this springhouse had a wooden plank door. The stone walls of the spring structure in the photo appear to have been parged. Tourists are shown in the photo using a ladle to obtain fresh spring water for a tin cup.[43]

Stairs leading up to the Springhouse suggest that the spring was used by people coming uphill from the canal. Perhaps it was used by canal workers who labored in the hot summer months on the canal or boatmen waiting their turn in the basin to go through the locks. There are also a couple of steps that allowed access to the spring from Canal Street.

Springhouse Stairs from Canal

|

| Lot 4: The Tavern Lot (Better known as Dickey's Tavern) |

Ruin of Dickey's Tavern

The business enterprise of William W. Williams and Company paid taxes on Lot 4 in 1797, though a deed recording a purchase of the lot was not discovered. It is evident that a building was already constructed on the lot by 1797 when the company was assessed a land tax equivalent to the tax paid by Joseph Gilpin on Lot 2.[44] It is unknown what kind of business William W. Williams & Co. operated at the building, though they weren't in business there for long.

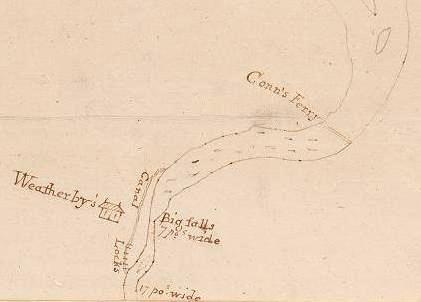

In 1798, Horatio Ross and Joseph Evans Rowles of Georgetown purchased lot 4 from Roger West.[45] It is unknown how West came into possession of the lot. James McCubbin Lingham purchased Horatio Ross's one half undivided interest in the lot that same year.[46] And at some point David Weatherly & Co. purchased the other one half undivided interest in the lot.[47] Weatherly's is depicted on a survey map of the Potomac River drawn in 1820 by Hugh P. Taylor.[50]

Part of a Potomac River Survey, Prepared by Hugh P Taylor, 1820, Image Courtesy Library of Virginia

David Weatherly & Co. obtained merchant licenses in 1818 and 1820, so it is possible the firm operated a store out of the building; however, Weatherly was operating a store elsewhere in the county prior to owning this lot so the fact that he obtained merchant licenses doesn't prove anything.[48] Certainly by January 1820, though, the building was operated as a tavern. At that time, David Weatherly entered into a trust agreement and used his interest in the lot as collateral. The agreement stated that the building was in the possession of William Hubball.[49] Hubball was a tavern keeper.

William B. Randolph purchased a half interest in the lot from the heirs of James M. Lingham in 1820.[51] Therefore, the lot was then owned jointly by David Weatherly & Co and William Randolph. They rented the house out to tavern keepers.

In 1821, Isaac Adams advertised that he opened a public house here. He called it the Great Falls Tavern.

GREAT FALLS TAVERN.

Isaac Adams respectfully informs his friends and the public that he has taken that most convenient House formerly occupied by David Weatherly & Co. The house being in good order for the accommodation of visitors, travelers, &c. he flatters himself that his attention to business will entitle him to a share of public patronage. Such as wish to visit the natural curiosities of this place can be accommodated with private rooms if required, and all necessaries both for themselves and horses.[52]

He did not remain the tavern keeper long. By April 1823, William Hubbell was again the tavern keeper. In letters to the National Daily Intelligencer and Alexandria Herald, visitors to the falls expressed their gratitude to Hubbell for his services.

...Our party had just reason for feeling greatly indebted to Mr. Hubbell, a young gentleman, lately from Alexandria, who has located himself conveniently to the falls, purposely to accommodate visitors, and whose polite attentions, united with those of his mother, ensured the best recption [sic] to us, and promise comfort and convenience to those making this delightful trip. Yours, &c. A.B.C.[53]

In February 1826, Hubbell was still operating the tavern, which he called a House of Entertainment. Hubbell is shown in the Personal Property Tax lists as having obtained ordinary (tavern) licenses.

House of Entertainment. GREAT FALLS OF THE POTOMAC. The subscriber respectfully informs the public, that he continues to keep a House of Entertainment, at the above named place, where he will be happy to accommodate such as visit this truly romantic spot; and pledges himself to use his utmost exertions to give satisfaction to those who may favor him with a call. He is always supplied with the best of liquors. &c. WM HUBBELL. Great Falls of Potomac, Feb 28 [54]

Hubbell's career at the tavern ended when Lewis Sewell purchased the interests of William Randolph and David Weatherly.[55] In 1829, Sewell set himself up as the tavern keeper. He enlarged and improved the structure and boasted that his stables were large and well supplied.

GREAT FALLS OF THE POTOMAC. The Subscriber now keeps that well known tavern, on the Virginia side of the Great Falls, lately occupied by Mr. Hubble. He has considerably enlarged and otherwise improved this establishment, so as to enable him to accommodate, with comfort and convenience, all who may honor him with their company. His stables are large and well supplied with provender of every kind. This tavern is not more than a half mile from the turnpike from Washington to Leesburg. Mar 23-2aw1stJune LEWIS SEWALL.[56]

In 1830, Sewell established a ferry across the Potomac River just below the Great Falls. A news article announced the opening of the ferry.

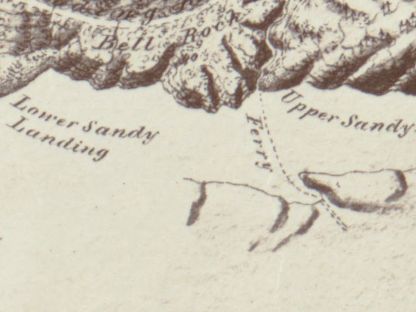

Sandy Landing

The Great Falls. - We are informed that a Ferry has recently been established for crossing the Potomac, just below the GREAT FALLS, and with a boat suitable for passing horses. The roads leading to this Ferry have been repaired, and a good public house established at the Falls on the Virginia side, by Mr. Sewall.

This will afford those who visit the Great Falls on horseback, either for pleasure or on business, the opportunity of seeing the works now in active operation upon the line of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal - as it is understood that the tow-path affords a good road, and no objection is made by the Company to its use as such.[57]

It is presumed that his ferry made land at Sandy Landing, shown on the 1866 map as the location of a ferry route.

1866 Map Showing Sandy Landing Ferry Route

Sewell advertised his ferry the following month, promoting the fact that the ferry afforded access to the falls.

NOTICE.

The inhabitants of Montgomery and Fairfax Countyies are informed that the subscriber has established a FERRY BOAT on the seventeenth section of the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, by which man and horse can be conveyed with safety and dispatch to the Great Falls. LEWIS SEWALL May 5[58]

Sewell also became the tavern keeper of the Crommelin Hotel on the Maryland side of the falls in 1831. He catered to parties seeking pleasure cruises in packet boats traveling on the C&O canal from Washington D.C.[59] Sewell became a toll collector for the canal and used his interest in Lot 4 as security to ensure the faithful discharge of his duties.[60] Sewell was no longer the proprietor of the Crommelin Hotel as of April 1833.[61]

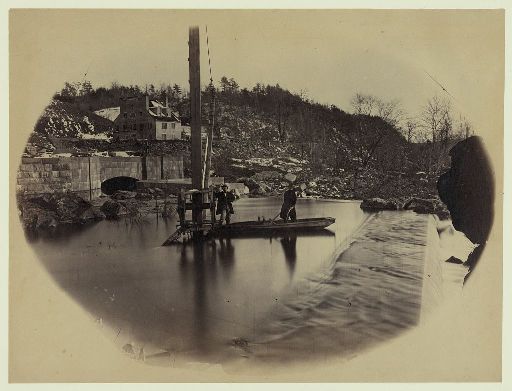

Crommelin Hotel in Background, Photographer Andrew Russell, ca. 1861 - 1865, Image Courtesy Library of Congress

Sewell's business ventures were unsuccessful, which resulted in the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Company obtaining a judgment against him for the sum of $1,768.[62] The tavern on Lot 4 was sold to Thomas ap C Jones by 1846.[63]

William P Dickey began operating the tavern around 1844 when he was about 34 years old.[64] He rented the property and operated the tavern almost continuously until he died, though William Henry obtained a one year lease on the tavern for the year 1854. Henry leased the tavern house and garden previously occupied by William P. Dickey for a yearly rent of $60. [65] Henry did not remain at the tavern long; by March 1854 he quit the business and William P. Dickey resumed as tavern keeper.[66] In addition to operating the tavern, Dickey was also listed as a carpenter in the 1860 census (he may have assisted in the construction of a nearby sawmill) and a farmer in the 1870 census.[67]

Postcard of Dickey's Farmhouse, Author's Collection

During the Civil War, Dickey's Tavern was briefly mentioned in reports about a July 1861 skirmish at Great Falls between Confederate soldiers on the Virginia side of the river who fired over at Major Gerhardt's Union battalion on the Maryland side.[68] Another minor action occurred in October 1861 near Great Falls involving Confederate soldiers on the Virginia side firing at Union soldiers on the Maryland side. During this affair, Union troops brought out a couple of Parrot guns and fired about six shots into Virginia, making the Confederate troops take flight.[69] William P Dickey's son, James H Dickey, was a captain in the Confederate army.[70]

William Dickey, who went by "Billy," was known to all of the tourists and fisherman who frequented the falls.[71]

Dickey's Hotel located near Great Falls

...we finally arrived at Dickey's hotel, near the Falls...[We] trusted ourselves in the hands of Mr. Dickey, who set before us in due time an excellent dinner, which we did full justice to; Mr. D, in the interim, had fitted out our tackle in first rate style, and dividing our party into two, reached the river at different points, and cast our lines with high hopes, but alas! had fishermen's usual luck. [72]

By 1880, William P Dickey's son, James H Dickey, was the head of the household.[73] William P Dickey died in 1887.[74] James Dickey continued the operation of the tavern and was also a farmer. He called his establishment at the falls Dickey's Farmhouse, which became a well-known sporting establishment catering to cyclists. After traveling to the Maryland side of the falls, visitors crossed the Potomac River about a half mile below the falls. Here they were met by the boatman from Dickey's who would row parties over to the Virginia side.[75] James H Dickey died in 1896 after months of poor health caused by being stricken while rowing a group of cyclists across the river.[76] The current was reported to be very swift, and the exertion likely brought on the attack.[77]

View of Ferry Landing on the Maryland Side at Top of Photo

James Dickey's widow, Julia, continued to operate the tavern and farm alongside her children who had been born in the tavern house. A newspaper article in 1901 gave a good description of the house.

...Built of rough-hewn boards, whitewashed over, propped up by huge chimneys, with a moss-covered shingled roof and a low, crooked veranda, hung with ferns and wood flowers, it is a good motif for an artist. All of the rooms are large, with low ceilings and up-and-down-hill floors, while the steps are worn almost to pieces. The dining-room is long and queer looking, a great long table in the center, a quaint, old-fashioned sideboard, and an old-time clock, while a series of strange and remarkable pictures graces the walls, such as "The Tree of Liberty," kings, queens, chromo ladies, and farms, very old and flyspecked. There are cracks in the walls large enough for streaks of light to shoot through, and in two or three places the vines on the outside have penetrated some old glassware on the sideboard and cling to the walls...There is fine country butter, all kinds of milk, sweet, fresh, sour, clabber, buttermilk, plenty of fried chicken, and garden vegetables, blackberry pie and coffee, enough and to spare...[78]

Outside of the house there were rowboats filled with dirt and planted with flowers, a ruin of a corncrib, and a springhouse. [79] President Theodore Roosevelt was among the many visitors over the years that enjoyed a chicken dinner at Dickey's.[80] Fried Chicken dinners were served at Dickey's until about 1935.[81]

Dickey's Farmhouse, 1930

After the Dickey family moved away, Mr. and Mrs. David Shiflett rented the house. They occupied the house from about 1936 to 1950 when a fire destroyed about two-thirds of the original log building. The fire department was able to save the frame addition that had been built onto the log structure.[82]

|

| Lot 6: Spring Lot |

|

Tobias Lear purchased Lot 6 in 1797, the same day he purchased six other lots. He paid 80 pounds for this lot, which was significantly higher than the average price for unimproved lots.[83] It appears that the two highest known amounts paid for unimproved lots were for the two lots with springs.

Land tax records do not indicate that any buildings were ever constructed on this lot.

|

| Lot 17: Ice House Lot |

1866 Map Showing Lot 17

Tobias Lear purchased Lot 17 in 1797.[84] This is likely the one lot he owned that had buildings constructed upon it. The buildings on this lot were valued at about half of the value assessed on the buildings on Lot 2 and Lot 4.[85] The 1866 Great Falls Manufacturing Map shows three structures, one of which is identified as an ice house. The large square shown on the map was the ice house.[86]

|

| Lots 21, 22, 25 and 26: Lear's Block |

|

In 1797 Tobias Lear purchased a block of four lots bounded by Canal Street, Washington Street, Lee Street, and Fairfax Street. The Potomac Company purchased lot 22 in 1803.[87] The other lots remained in the Lear family.

Tax records do not show any indication that buildings were constructed on lots 21, 25, or 26. The Potomac Company may have constructed buildings on lot 22.

|

| Lot 23: Potomac Company House |

1866 Map Showing Lot 23

By 1821 the Potomac Company owned three lots. The Company had the greatest investment in buildings in the town. The assessed value of buildings on all three lots was $1,000 in 1821 compared to the value of the tavern on Lot 4 of $400.[88]

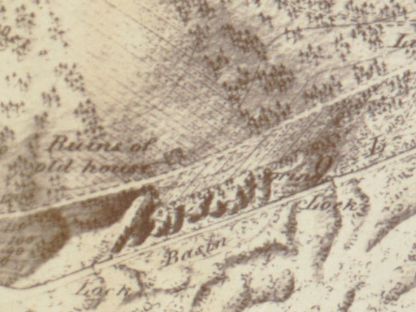

It is hypothesized that the Potomac Company purchased this lot, through there is no record. The hypothesis is substantiated by the fact that a house was constructed on the lot by 1866 when a ruin of the old house was depicted on the Great Falls Manufacturing Company map. Land tax records show lot ownership and indicate which lots had buildings. By a process of elimination, it appears that the only candidate left for ownership of this lot is the Potomac Company who also owned the next lot over. Perhaps the Potomac Company constructed workmen's housing closer to the canal locks.

|

| Lot 31: Gilpin/Wiley Lot |

|

In 1797 Joseph Gilpin purchased lot 31 from the trustees of the town of Matildaville.[89] He sold the lot to William Wiley in 1801.[90] William Wiley was the son of James Wiley, one of the early town trustees. There is no indication in the tax records that a structure was ever built on this lot.

|

| In the End |

|

The success of the town of Matildaville was tied to the success of the Potomac Canal. The canal venture was not financially viable due to water levels in the river that limited use of the canal to only one or two months per year, plus the frequent need for costly repairs. The Potomac Canal was ultimately sold to the Chesapeake & Ohio Canal Company who began construction of a different type of canal system on the Maryland side of the river in 1826.[91] After abandoning the Virginia canal at Great Falls, it appears that the land reverted to Albert Fairfax, heir of the original land owner.

The land at the Great Falls was sold at auction in 1838. Lot 1, consisting of 963 acres was auctioned off to Thomas ap C Jones, who may have been representing the Great Falls Manufacturing Company.[92] It was the vision of the Great Falls Manufacturing Company to create a water-powered manufacturing town similar to the textile manufacturing town of Lowell, Massachusetts.[93]In 1839 the Virginia General Assembly passed an act to establish the town of South Lowell on land owned by men associated with the Great Falls Manufacturing Company. The town could not exceed 300 acres, and town trustees were required to prepare a plat of the town. The act repealed the charter for the town of Matildaville. [94] Another auction of land belonging to the heirs of Albert Fairfax was conducted in 1851. The Great Falls Manufacturing Company became the purchaser of 761 acres of land that extended above and below the falls.[95]

The Great Falls Manufacturing Company began selling stock in the company in 1853.[96] The company ran into difficulties in 1858 when the United States Government argued in court that the Great Falls Manufacturing Company did not have water rights since the river belonged to Maryland, and was therefore not entitled to divert water. The company argued that they had rights to the water on the Virginia side of the low water line.[97] Although the Great Falls Manufacturing Company made some improvements to the old canal and constructed a saw mill, they were never able to attract manufacturing companies.

The town of South Lowell became known as Potomac by 1857.[98] Most of the houses and structures were abandoned over time except for Dickey's Tavern, which was eventually destroyed by fire. Today, all that remains of the town of Matildaville are the ruins of the houses and outbuildings, and Canal Street, which is now used as a walking trail through Great Falls Park.

[1] Authorization by the Virginia General Assembly to form the Town of Matildaville was part of An Act to Establish Several Towns, which passed on December 16, 1790 per Loudoun County Deed Book Y:238. The first trustees of the town were George Gilpin, Albert Russell, William Gunnell, Josiah Clapham, Richard Bland Lee, Levin Powell and Samuel Love. Albert Russell, Richard Bland Lee, and Samuel Love resigned soon thereafter and were replaced by Thomas Gunnell, John Jackson, and James Wiley. [2] John Pickell, A New Chapter in the Early Life of Washington, in Connection with the Narrative History of the Potomac Company., D. Appleton & Co, New York, 1856, p. 156. Courtesy Google Books. [3] Cynthia Miller Leonard, The General Assembly of Virginia July 30, 1619 - January 11, 1978: A Bicentennial Register of Members, Virginia State Library, Richmond, 1978. [4] Pennsylvania Mercury, August 26, 1790, p. 3. [5] John Davis, Travels of Four Years and a Half in the United States of America; During 1798, 1799, 1800, 1801, and 1802, R. Edwards, Printer London, 1803, p 340, Online access courtesy Library of Congress. [6] "Country Homes for Cityites Within Sight of Washington," The Washington Post, June 4, 1911, p. C2. [7] Lieut. Francis Hall, Travels in Canada, and the United States in 1816 and 1817, Printed for Longman, Hurst, Rees, Orme, & Brown, London, 1818, p 340, Online access courtesy Library of Congress; Also, Statistical, Political, and Historical Account of The United States of North American; From the Period of their first Colonization to the Present Day, Vol. III, Printed for Archibald, Constable, and Co, Edinburgh, 1819, p. 187; Also, R. Brookes, M.D., The General Gazetteer; or Compendious Geographical Dictionary., 17th ed., Printed for F. C. and J. Rivington, et. at., London, 1820, listed under POT (no page numbers). Courtesy Google Books. [8] Lease dated September 3, 1793 is located in Fairfax County Chancery # 1832-006. [9] Fairfax County Land Tax Ledgers 1807 and 1809, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, VA. [10] J. De la Camp, A Topographical map of the Estate of Great Falls Manufacturing, Fairfax Co., Va., 1866, Courtesy Library of Congress American Memory. [11] See Fairfax County Deed Book V3(74)17. [12] Authorization by the Virginia General Assembly to form the Town of Matildaville was part of An Act to Establish Several Towns, which passed on December 16, 1790 per Loudoun County Deed Book Y:238. [13] Loudoun County Deed Book Y4:1, 4, 8, July 15, 1797. [14] Loudoun County Land Tax Ledgers 1797-1798, Fairfax County Land Tax Ledgers 1800 onward, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, VA. [15] Loudoun County Deed Book X:434, December 26, 1793. A deed for lease from Henry Lee to George Gilpin notes that the land on the south and east of that lot was acquired by the Potomack Company through condemnation. It is assumed through deduction that the leased lot was Lot 2. [16] Columbia Historical Society, Records of the Columbia Historical Society, Washington, D.C., Compiled by the Committee on Publication and the Recording Secretary, Volume 15, Columbia Historical Society, Washington, 1912, p. 182, as viewed on Google Books. [17] Federal Gazette, July 22, 1796, p. 4. [18] Fairfax County Personal Property Tax for 1798, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [19] Alexandria Times, August 18, 1797, p. 4. [20] Columbian Mirror, May 13, 1798, p. 4. [21] Columbian Mirror, August 31, 1799, p. 4. [22] John Davis, Travels of Four Years and a Half in the United States of America; During 1798, 1799, 1800, 1801, and 1802, R. Edwards, Printer London, 1803, p 340, online access courtesy Library of Congress [23] United States Federal Census for 1850. [24] Fairfax News, June 13, 1873, p. 2. [25] Daily National Inteligencer, September 11, 1845, p. 2. [26] Fairfax County Chancery # 1899-004. [27] Fairfax News, June 13, 1873, p. 2. [28] Loudoun County Deed Book X:434, December 26, 1793, microfilm, Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA. [29] Loudoun County Land Tax 1797, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [30] Loudoun County Deed Book X:434, December 26, 1793, microfilm, Thomas Balch Library, Leesburg, VA. [31] Loudoun County Deed Book Y:238, February 24, 1797, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [32] Fairfax County Deed Book A2(27)494, December 15, 1790; Also, Centinel of Liberty, May 31, 1796, p. 4. [33] Fairfax County Personal Property Tax Ledgers 1798, 1799, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [34] Fairfax County Land Tax Ledger 1814, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [35] Fairfax County Land Tax Ledger 1823, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [36] Fairfax County Land Tax Ledger 1824, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [37] Fairfax County Deed Book W2(49)113, September 20, 1825. [38] Fairfax County Deed Book I4(87)249, June 13, 1868. [39] Fairfax County Deed Book K4(89)274, March 6, 1869. [40] Fairfax County Deed Book A2(27)494, July 15, 1797. [41] Fairfax County Deed Book B2(28)232, May 15, 1798. [42] Fairfax County Land Tax Ledgers 1797 - 1866, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [43] "Beautiful Scenery and Historic Relics "Snapped" on the Upper Potomac," The Washington Post, p. SM12. [44] Loudoun and Fairfax County Land Tax Ledgers 1797 - 1800, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [45] Fairfax County Deed Book A2(27)306, May 15, 1798. [46] Fairfax County Deed Book A2(27)431, July 11, 1798. [47] Fairfax County Deed Book W2(49)221, January 28, 1820. Trust agreement used lot as security. [48] Fairfax County Personal Property Tax ledgers 1818 and 1820, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [49] Fairfax County Deed Book W2(49)221, January 28, 1820. Trust agreement used lot as security. [50] Hugh P. Taylor, Map of Potomack River from Harpers Ferry to Alexandria, Virginia, Board of Public Works Collection, Library of Virginia, Richmond, Virginia. [51] Fairfax County Deed Book S2(45)123, August 29, 1820. [52] Daily National Intelligencer, June 4, 1821, p. 2. [53] National Daily Intelligencer, April 19, 1823, p. 2; Also, Alexandria Herald, May 2, 1823, p. 2. [54] Alexandria Gazette, March 1, 1826, p. 3. [55] Fairfax County Deed Book Y2(51)64, April 30, 1828; Also, Land Fairfax County Land Tax Ledgers of 1829 and 1830, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [56] Daily National Intelligencer, April 10, 1829, p. 2. [57] Daily National Intelligencer, April 16, 1830, p. 3. [58] Daily National Intelligencer, May 10, 1830, p. 1, col. 5. [59] Alexandria Gazette, June 21, 1831, p. 3. [60] Fairfax County Deed Book B3(54)68, October 1, 1832. [61] "Union Grand Canal May Ball, Crommelin Hotel, Great Falls of Potomac, Alexandria Gazette, April 30, 1833, p. 3. [62] Fairfax County Deed Book B3(54)421, May 21, 1835. [63] Fairfax County Land Tax Ledgers of 1842 and 1846, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [64] The Washington Post, November 19, 1887, p. 3. Obituary of William P. Dickey states that he lived on the Virginia side of the Great Falls in the same spot for 43 years. [65] Fairfax County Chancery 1899-004, January 1, 1854, p. 32. [66] Fairfax County Chancery 1879-015, p. 15. [67] Federal Census of 1860 and 1870. [68] Daily National Intelligencer, July 9, 1861, p. 3. [69] Richmond Enquirer, October 12, 1851. [70] The Washington Post, October 21, 1896, p7 [71] The Washington Post, November 19, 1887, p. 3, obituary for William P Dickey. [72] "Dickey's Hotel Located Near Great Falls," Fairfax News, June 13, 1873, p. 2. [73] Federal Census of 1880. [74] The Washington Post, November 19, 1887, p. 3, obituary for William P Dickey. [75] "Falls are Wiped Out," The Washington Post, March 2, 1902, p. 2. [76] The Washington Post, October 21, 1896, p7 [77] "Stricken Down in His Boat," The Washington Post, February 18, 1896, p. 8. [78] "Trip to Great Falls," The Washington Post, July 14, 1901, p. 28. [79] "Trip to Great Falls," The Washington Post, July 14, 1901, p. 28. [80] "Who Remembers," The Washington Post, November 23, 1924, p. EF1. [81] "Lee-ward Bound," The Washington Post, March 27, 1987, p. W4. [82] "Fire Damages Dickey House on the Potomac," The Washington Post, June 23, 1950, p. B1. [83] Loudoun County Deed Book (LN DB) Y4:1, July 15, 1797. [84] Loudoun County Deed Book (LN DB) Y4:8, July 15, 1797. [85] Fairfax County Land Tax Ledger, 1820-1839, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [86] An ice house is shown in this article; however, it is likely not Lear's ice house due to the smaller size of the icehouse shown. "Beautiful Scenery and Historic Relics 'Snapped' on the Upper Potomac," The Washington Post, October 14, 1917, p. SM12. [87] Fairfax County Deed Book E2(31)232, January 21, 1803. [88] Fairfax County Land Tax Ledger, 1821, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. [89] Loudoun County Deed Book Y:238, February 24, 1797. [90] Fairfax County Deed Book C2:380, 1801, Index. Deed book is missing. [91] Fairfax County Deed Book Y2(51)26, August 15, 1828. [92] Fairfax County Chancery 1838-005, August 6, 1838. [93] Alexandria Gazette, November 21, 1853, p. 2. [94] Acts of the General Assembly of Virginia: Passed at the Session Commencing 7th January, and Ending 10th April, 1839, Chapter 248, Samuel Shepherd, Printer to the Commonwealth, Richmond, 1839, p. 184. [95] Fairfax County Deed Book V3(74)17, 1854. [96] Alexandria Gazette, August 19, 1847, p. 3. [97] Daily National Intelligencer, December 17, 1858, p. 3. [98] Fairfax County Land Tax Ledger, 1857, microfilm, Virginia Room, Fairfax County Public Library, Fairfax, Virginia. |

| Home |

|